Makerspaces Carve Out a Niche with Pros

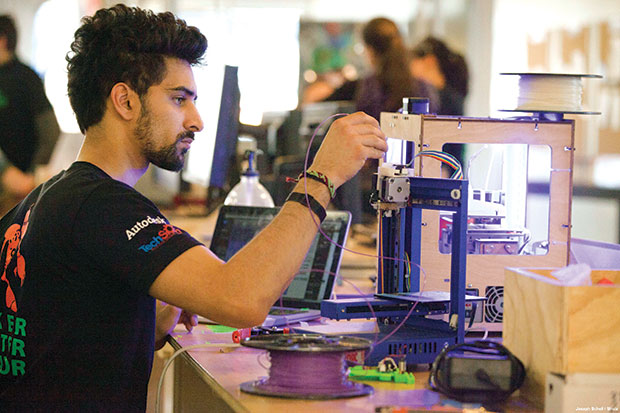

These spaces can help startups create prototypes via 3D printing and other fabrication methods. Image courtesy of Joseph Schell.

June 1, 2015

These spaces can help startups create prototypes via 3D printing and other fabrication methods. Image courtesy of Joseph Schell.

These spaces can help startups create prototypes via 3D printing and other fabrication methods. Image courtesy of Joseph Schell.Square, the mobile payment company that first gained notice with those little credit card swipe accessories for smartphones, has come a long way since founders Jack Dorsey and Jim McKelvey walked into TechShop, a California-based makerspace. Leveraging the tools and community members in the facility, they were able to quickly develop a prototype of their first credit card reader. The company now has a nearly $6 billion market valuation.

While makerspaces have been a boon for students, hobbyists and artists, they’ve also become an invaluable resource for professional engineers and designers. Whether they were designed that way from the start or have evolved and expanded their services, makerspaces are acting as hands-on manufacturing incubators for startups of every stripe. They also offer a place for engineers to add to their training, tinker with new ideas outside of their day jobs and even provide facilities for large, established companies to brainstorm and prototype.

Square is probably the most well-known example, but there are plenty of others. DODOcase, another TechShop alum, sold its first $1 million in product 90 days after founder Patrick Buckley walked through the door. “Our best bet is about 2,000 jobs have been created through our facilities, along with $2 billion in annual sales and $200 million in salaries created from our members developing and launching companies,” says TechShop CEO Mark Hatch. The organization now has eight locations across the country, with more in the works.

At the Columbus Idea Foundry in Columbus, OH, a host of professionals have called the makerspace home, including local 3D printer company IC3D, and 3D scanner maker Knockout Concepts. Having just moved into a 65,000 sq. ft. warehouse space in 2014, the Idea Foundry offers a traditional tool-laden makerspace on its ground floor. It is in the process of raising funds to add more professional services upstairs, including space for graphic artists, Web developers and trademark attorneys.

“The idea is that you use the first floor to build your widget, and then go upstairs and get the professional help you need on the business and legal side to launch a company,” says Alex Bandar, founder. “It’s really a one-stop-shop, creative ecosystem.”

Artisan’s Asylum in Somerville, MA, was originally launched by a group of engineers who wanted to have access to the same fabrication equipment in their personal lives that they did at work, says Derek Seabury, president and executive director. As the facility grew, so did the appeal for professionals.

“The value proposition emerged for a cabinet maker or a contractor, or for someone doing prototyping,” Seabury says. The space’s most well known startup is probably the 3Doodler, a 3D printing pen that went on to a successful Kickstarter-funded launch.

The appeal is clear: Makerspaces offer, for a nominal membership fee, access to equipment and expertise that would require thousands (or hundreds of thousands) of dollars to obtain for traditional product development. Inventors can launch a product with a relatively small amount of disposable income rather than taking out a large loan or raising capital.

Expanding Professional Services

Makerspaces have made their facilities more hospitable to professional engineers, even as they continue to offer space for amateurs and hobbyists. Most, for example, even offer institutional memberships for companies that want their employees to have access to these less formal workspaces.

“The original appeal was around some newer technologies,” Seabury says. “Not every company was able to invest in a 3D printer or a laser cutter, so this gave them a way to access the equipment without the big upfront cost.”

Sometimes these services evolve organically. At TechShop’s original Menlo Park location, members asked to rent some empty office space that happened to be vacant; now every TechShop offers office space for engineers and startups.

Makerspaces, such as TechShop, give designers and engineers access to professional-grade machines that would be expensive to purchase otherwise.

Makerspaces, such as TechShop, give designers and engineers access to professional-grade machines that would be expensive to purchase otherwise.Makerspaces also provide relatively unfettered access to pro-level software tools (see Supplying Software on page 46). TechShop, for instance, actively pursued a relationship with Autodesk to provide software on their in-house workstations. “Some of their executives came for a tour, and they got excited about the concept,” Hatch says. “Within a few weeks [TechShop founder] Jim Newton and I were sitting down with their CEO and we struck a deal right there.”

Because many of the professional members are doing work after hours, TechShop recently opened its locations 24/7. “That was in direct response to our heavy use members, which tend to be startups and engineering firms,” Hatch says. “There was no real reason we had to kick them out at midnight. If someone needs to use the computer in the middle of the night, they should be able to do it.”

While the core appeal of makerspaces to engineers is access to tools, most also provide other types of services that can be helpful to startups and inventors. TechShop has developed a relationship with the Patent and Trademark Office that has helped put members in touch with an actual patent examiner to determine if an idea is patentable. Regular meetups also provide instruction on website design and financial services, among others.

“We’ve become something of a hotbed for service companies that are interested in taking care of startups, and we’re a conduit for enabling that,” Hatch says.

In some instances, makerspace staff can be hired for light engineering or manufacturing services, and the facilities can be used for small production runs. New companies can also get help from other members in different specialties to help with logo designs, marketing or manufacturing. In many cases, members wind up hiring each other.

“The community itself has become quite a gathering of experts,” says Seabury at Artisan’s Asylum. “You can network and get advice, and it’s a different experience than you would have in an incubator. It’s a more collaborative space. Part of our membership charter is that you will share your skills and describe processes with other members, and accept feedback gracefully. We’ve had folks come in who spent time in a traditional incubator and told us that they got more answers in two weeks here than in two years at an incubator.”At Artisan’s Asylum, the makers of the 3Doodler received unexpected help from an artist operating in the building. “Not only were they able to find an electrical engineer to help debug some issues with the power driver, but we had a wire artists here that showed them they types of amazing things she could achieve with the product,” Seabury says.

The company was able to use the wire frame art pieces created with the pen to show investors what it was capable of doing.

Once a company has reached the tipping point where they need to move thousands instead of hundreds of units, the makerspace can help find that manufacturing capacity. Other members from different industries may also provide help with identifying contract manufacturing facilities.

By fostering engineers, makerspaces have been able to have an impact beyond their own four walls. At the Idea Foundry, Bandar has worked with the city of Columbus to turn the makerspace into an economic development engine. The Foundry sits in an economically fragile area near downtown, and is actively working to create jobs and development opportunities that can benefit the surrounding community while allowing the city to plant a flag as a destination for maker culture. Some of the companies that have spun out of the Foundry have followed suit.

Big Companies, Small Spaces

Large existing companies have also discovered that makerspaces can serve as outsourced skunkworks or prototyping facilities. While it seems odd that a multi-national company would join a co-op style studio, many have found that it is more efficient to let designers knock out models and prototypes at a makerspace than trying to carve out time in their own production facilities.

“Xerox uses our local facility’s waterjet cutter because they don’t have one and it’s faster to come down and cut something out here,” TechShop’s Hatch says. “Mercedes uses our Palo Alto facility to build displays for their software research group. We have corporate members with a wide array of large and small companies that use us as a support mechanism for their own product development.”

Ford, in fact, brought TechShop to Detroit specifically for that reason. “They brought us so that engineers who weren’t directly involved in R&D could build prototypes,” Hatch says.

In Columbus, local Idea Foundry sponsor VSP Global (which operates a high-tech optical lab in the city), uses the facility for “intrapreneurship.” “They can send their employees offsite to work in a judgment-free zone, rather than having to build their own innovation center,” Bandar says. “These larger companies want their engineers to be able to keep an ear to the ground in a place where the other members are up on the latest trends.”

Those relationships also provide access to experienced engineers for the startups and hobbyists in the space. “You have this multi-layered environment of very large corporations and new startups operating under the same roof,” Bandar says. “It’s a huge value-add for them to go over to a guy from a big company and talk to them about an idea. It’s rare to see that type of intermingling outside of a makerspace.”

All of this begs the question: Do these startups risk their IP (intellectual property) in an environment where prototypes are quite literally being passed around a room full of other inventors and startups? So far, the answer seems to be no.

“You have all this amazing work going on in every room, and it’s not generally felt that being secretive or first to market is as important as excellence,” Seabury says. “I guess we could be ripe for corporate espionage, but I think that the ability to execute on the plan is more important than the plan these days.”

What has mitigated that type of competitive elbowing seems to be that most of the members are working with established technology, and often developing products in different markets. “Some of our members might go head-to-head for some business opportunities, but the space to achieve is really vast,” Seabury says. “We have four different people right now working on 3D printers, and none of them feel the need to throw a sheet over things at the end of the night. They aren’t threatened by other inspired, passionate people. The bigger threat would be an uncreative entity that can take that idea away and execute on it, and we don’t have many of them stumbling around a makerspace.”

More Info

Subscribe to our FREE magazine, FREE email newsletters or both!

About the Author

Brian Albright is the editorial director of Digital Engineering. Contact him at [email protected].

Follow DE